Winter is finally over and I spent a lot of it reading. I read 7 books in total this year so far. They are:

1. Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage, Haruki Murakami

This was the first book I read this year, which meant I ended 2023 and began 2024 with two different Murakami novels, After the Quake and this book respectively. I read most of Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki sitting overnight in a hospital ER, so part of me will always associate this book with the sleepy, slow moving air of a waiting room at night. The novel spans a couple decades of Tsukuru Tazaki’s life after he gets suddenly dropped by his beloved group of friends. It follows him as he heals from this trauma and reconciles with them and himself enough to risk deep and meaningful connection again.

I found this to be the most realistic and human Murakami novel I’ve read so far, in contrast to more emotionally dissociated magic realism of his other books.

2. Breasts and Eggs, Mieko Kawakami

In Breasts and Eggs, Kawakami writes about 3 different women— the narrator, Natsuko, her sister, Makiko, and her niece Midoriko— as they navigate some very different ways a woman can experience life and a relationship with her body. They are surrounded by yet more women, each mirroring a different yet realistic life path women in the real world may take. They present crucial questions most of us eventually find ourselves asking, like, ‘Is it worth it to get married and/or have children?’, ‘What defines a woman’s worth?’ and ‘How can we justify having children in a world full of potential suffering?’

While Natsuko eventually makes choices that offer her a semblance of peace, the kaleidoscope of possibilities in Breasts and Eggs invites readers to think for themselves and craft their own answers.

3. White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard For White People to Talk About Racism, Robin DiAngelo (audio book)

Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility verbalises all the frustrating, belittling and dehumanising racist encounters big and small anyone living as a minority has already experienced a million times before they even begin reading this book. It not only talks about outright, hateful racism, it also exposes ‘aversive racism’. This refers to the fake and condescending, more subtle racism in which the culprit insists on their benevolence and innocence while inflicting equal amounts of— if not more— damage.

I found this book incredibly validating; it is comforting to know that when someone is being racist to me, and treats me like I am less than—simply for the way I look— it is not all in my head. Instead, it is real and the outcome of centuries of psychosocial conditioning which makes the other person feel (however subconsciously) that they have the right to treat me this way with absolutely no shame or apology on their part. It is a reminder that I am not being dramatic or hysterical— what I experience is real and wrong. White Fragility reminds us that every member of a majority race is personally responsible for reducing the racism-inflicted suffering minority races endure on a daily and persistent basis. She also gives some good points to members of both minority and majority races on how to navigate the sensitive but essential effort to reduce racism.

4. Burnt Sugar, Avni Doshi

In Burnt Sugar, Avni Doshi writes about Antara and her mother Tara. When Antara was growing up, she suffered from Tara’s abuse and neglect. Now, as an adult child, Antara finds herself in the unexpected and seemingly inescapable position of caretaking for this same mother, now senile and ageing. In Antara’s desperation to disentangle herself from the enmenshed and destructive mother-daughter bond, she becomes increasingly trapped. Overtime, she loses clarity and perhaps even her mind as the the boundaries between her mother and herself blur and dissolve.

5. Crime and Punishment, Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoyevsky is an incredibly wise, human and observant book. Its main focus is the murder Ralskonikov commits and the ways he is punished for it. It also presents other characters with parallel stories, each of them a foil to Ralskonikov’s central storyline and character. The novel straddles fiction and philosophy— the story serves as the platter on which Dostoyevsky poses a plethora of philosophical conundrums and questions. These concern: murder, vice and morality (crime and redemption), punishment, beauty, friendship and family, to name a few. Each one of these has multiple possible answers and results. The characters then seem to play assigned roles meant to illustrate and conduct these philosophical experiments to their extremes and logical conclusions.

Throughout, Dostoyevsky infuses the book with the beauty, tragedy and fragility familiar to all who take the time to pay attention to life and the multitudinous ways it can break a person and their heart.

6. Blue Nights, Joan Didion (audio book)

Blue Nights meanders through Didion’s memories as she grieves her late daughter Quintana. Grief, the sorrowful dimension of love, takes her to certain key memories again and again: Quintana’s adoption and wedding and her childhood quirks and fears. Didion’s memories are scaffolded by certain sayings and scenes, like the flowers in Quintana’s hair, odd and loveable things she used to say, or the colour of the sky. Towards the end of Blue Nights, Didion also confronts her own ageing mind and body and the painful reality of old age without her daughter to hold on to, to love and to be loved by.

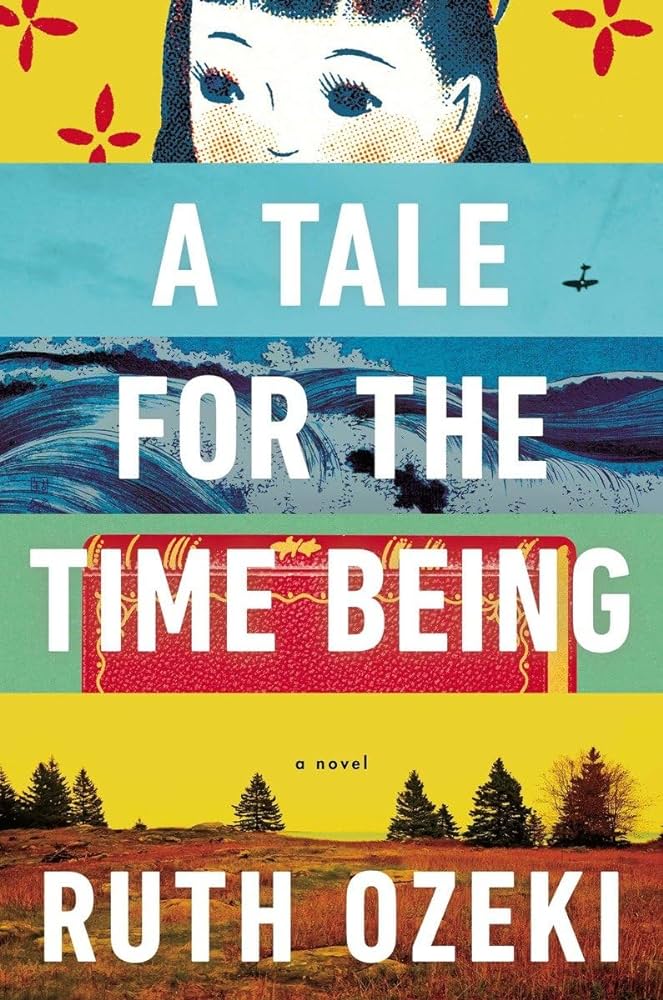

7. A Tale for the Time Being, Ruth Ozeki

Ruth Ozeki’s A Tale for the Time Being is a lovely and thoughtful read, a nice contrast to the heavier books I read preceding it. It is told from two voices: Naoko (Nao), who writes in a diary in Tokyo and Ruth, who finds it mysteriously stranded on a beach in faraway Vancouver Island. Nao writes about the turmoil in her school and home life, and how she managed to find some solace when she spends a summer at her great-grandmother Jiko’s Zen Buddhist temple. When she returns to reality, she struggles to apply the wisdom she gleaned from Jiko. As Ruth follows Nao’s story, she is likewise tested and tried.

A Tale for the Time Being plays with multiple concepts like the traditional author-reader power dynamic, quantum mechanics and Zen Buddhist teachings. Ozeki proposes that we are more interconnected, and have way more agency, than we think. That we do not just read our lives as they happen to us. We write them too.