“You are my hiding place; You shall preserve me from trouble; You shall surround me with songs of deliverance.” – Psalm 32:7

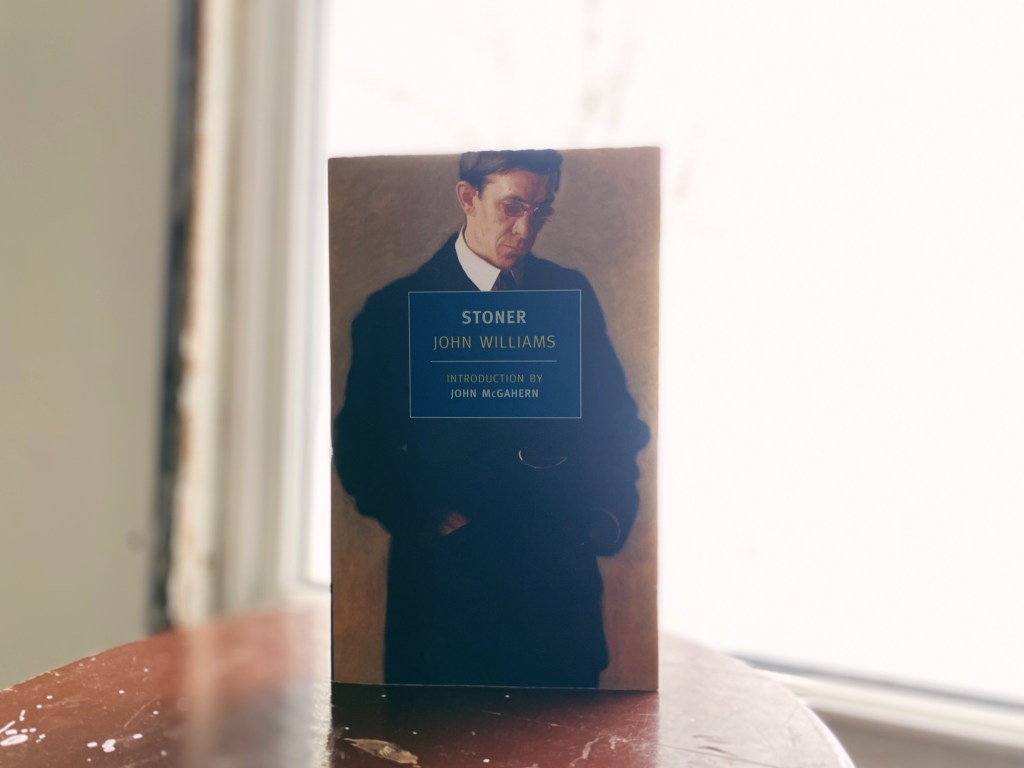

John Williams’ Stoner tells the story of titular character William Stoner’s life, from the time he matriculates into the university of Missouri to his death. The first line of the novel reads, “William Stoner entered the University of Missouri as a freshman in the year 1910, at the age of nineteen” (3). Fittingly, the novel begins where Stoner’s life as it matters begins, when he first enters academia, an institution that eventually defines him to the extent that there is no “him” beyond it. Stoner’s life and mind beyond academia’s borders are fuzzy, passive and dissociated. As his marriage and family fall apart, as society burns around him, he hides in academia both literally and figuratively. Like David’s song in the Psalm above, Stoner makes academia his refuge, shelter and deliverance.

Academia vs Life

Stoner is divided into 17 chapters, each containing the key details of a chapter in William Stoner’s life. Throughout, academia appears to be its main star, a stable, reassuring presence ; it is more or less unchanging with just a few hiccups here and there. In the backdrop, however, his life happens around him and the main tragedies and mishaps that occur in it become more visible only by tracking its chapters. In chapter one, we see how he uproots himself from his family of origin and plants himself firmly into the soil of academia. It portrays the first time he is fully conscious, i.e., the moment he falls in love with literature: “William Stoner realised that for several moments he had been holding his breath. He expelled it gently, minutely aware of his clothing moving upon his body as his breath went out of his lungs” (13). He comes to life. Throughout the book, he continues to only show any signs of passion within the institute of academia.

In his ‘real life’ beyond the campus however, Stoner sits passively, his eyes glazed over; he barely lifts a finger to evoke or prevent anything: “more and more often he found himself staring dully in front of him, at nothing; it was as if from moment to moment his mind were emptied of all it knew and as if his will were drained of its strength. He felt at times that he was a kind of vegetable, and he longed for something— even pain— to pierce him, to bring him alive” (179).

Stoner functions like two different men, his mind and self are so completely ensconced in his hiding place that he is oblivious to all else. There is a moment which comically and saliently encapsulates this duality, when he is so “engrossed in translating extemporaneously a pertinent Latin passage” during a lecture that he fails to notice the president of the University and four men trying to tell him that they need his conference room for a meeting. “Without a break or pause in his extemporaneous translation, Stoner looked up and spoke the next line of the poem mildly to the president and his entourage: ‘Begone, begone, you bloody whoreson Gauls!’ And still without a break returned his eyes to his book and continued to speak, whill the group gasped and stumbled backward, turned and fled from the room” (231).

Even Stoner’s love affair is only possible because it was founded in and defined by his and his lover Katherine’s identities and existences in academia. Eventually, he gives the affair up, choosing to stay in town while Katherine leaves, because, he explains, if they start anew elsewhere, “none of it would mean anything— nothing we have done, nothing we have been. I almost certainly wouldn’t be able to teach, and you— you would become something else. We would both become something else, something other than ourselves. We would be— nothing… Because in the long run, it isn’t Edith or even Grace [his daughter], or the certainty of losing Grace, that keeps me here… it’s simply the destruction of ourselves, of what we do” (214-5). Stoner is aware that teaching is what gives him his shape and form; that what he does is what he is. Although it is never explicitly stated, he seems content to let that be all he is, and to be a gray blur everywhere else.

Academia requires that a person progressively devotes themselves wholly and only to one subject matter. With Stoner’s specialty, the Latin Tradition and Renaissance Literature and Middle English Language and Literature, as with many other branches of literature, the subject at hand is usually so abstract and removed from the everyday that it has no practical value. Stoner takes the academic ethic to the extreme and literal, devoting himself to his craft to the detriment of his actual life.

The chapters in Stoner are numbered using Roman numerals, like a clock in the background keeping track of Stoner’s life even as he lets it slip by, ticking away the time that erodes at everything— his relationships, career and eventually his body and identity as an academic and scholar.

Before Stoner’s friend Dave Masters dies, he makes a declaration over Stoner’s life, calling him out for using the University as a hiding place from a world he is too cowardly to confront. Masters declares, “it’s for us that the University exists, for the dispossessed of the world; not for the students, not for the selfless pursuit of knowledge, not for any of the reasons you hear” (32). Indeed, when Stoner himself is about to die, he looks not to Edith, or the rest of the world. He looks for his one modest published book, looking for “a small part of [himself]” (277), tucked away into a practically meaningless pursuit and subject matter. Into a long forgotten text that is the physical representation of an imagined identity. He comes alive in the book’s presence for one last time. As the book tumbles symbolically to the ground, Stoner breathes his last and ceases, at last, to exist.

One thought on “Stoner, John Williams: Academia as an Appropriation of Life”