“At that moment, the pool was terrifically deep. Deeper and deeper as watery blue darkness seeped up from the bottom. The knowledge, so certain it was sensuous, that nothing was there to support the body if one plunged in generated around the empty pool an unremitting tension. Gone now was the soft summer water that received the swimmer’s body and bore him lightly afloat, but the pool, like a monument to summer and to water, had endured, and it was dangerous, lethal”

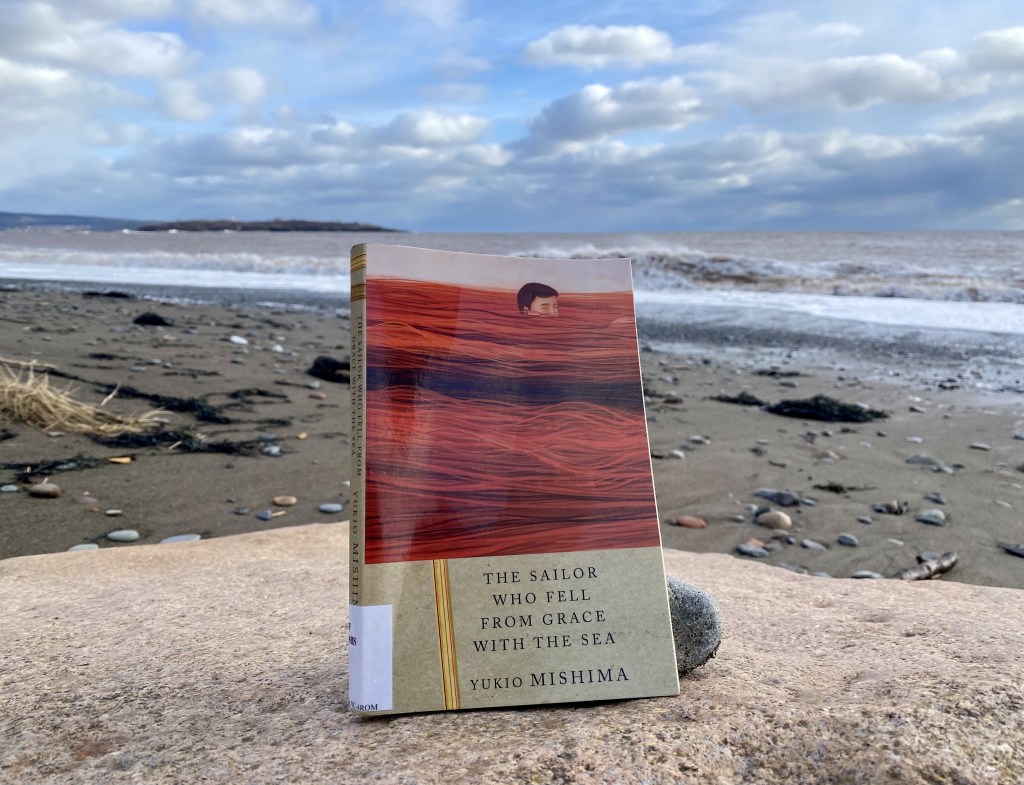

Yukio Mishima, The Sailor Who Fell From Grace with the Sea

It’s been a while since I’ve read something that moves me to write about it. Yukio Mishima’s The Sailor Who Fell From Grace with the Sea is such a contradiction that I can’t stop thinking about it more than a month after reading it. On the one hand, it is filled with the same pretty detail to natural and manmade surroundings I adored in The Sound of Waves. On the other, the novel portrays a striking conundrum: a dark vein of perversion winding through its pastoral landscape.

The Sailor Who Fell From Grace with the Sea tells the story of thirteen-year-old Noboru. Noboru hangs out with a group a boys regularly. His father died during the war and when he asks to go on a ship that docks in their town, his mother and a sailor from a ship fall in love and start planning their wedding. The novel is told as a comprehensive whole by a third-person narrator. However, there are arguably two perspectives of the events that occur and the world they occur in. Noboru’s mother Fusako sees Noboru as merely a thirteen-year-old boy with some friends. When she brings Ryuji the sailor home and eventually tell Noboru they are getting married, she does so with the expectation that Noboru is a child; a teenager with normal moods and interests, such as ships and a wish for a father figure.

Unbeknownst to Fusako, Noboru and his friends are far from normal. From their discussions of their home lives, these are boys who have been deeply hurt by their parents, especially their abusive and/or neglectful fathers. While it is not explicit, their actions and discourse suggest that they have dealt with this by trying their best to shed their humanity.

On the mildest end of this attempt, they do not address each other by their names but by numbers. Noboru is number three and the leader is known by ‘chief’. The chief leads them in exercises aimed to desensitise them to bodily reactions, by showing them porn magazines and encouraging the boys to be above normal base reactions. It does not stop there. The chief leads them to kill a kitten: “At last the test of Noboru’s cold, dark heart!… Noboru seized the kitten by the neck and stood up. It dangled dumbly from his fingers. He checked himself for pity… it flickered for an instant in the distance and disappeared. He was relieved” (57). The chief then slices the kitten open and makes the boys stare into its insides, praising Noboru and telling him that this has finally made a man of him. The boys play god, exercising power over death as a right and as proof that they are above others, a special, called-out breed, ‘geniuses’ (161).

At the same time, they remain hurt little boys, and their denouncement of the world and of humanity is their misguided attempt to numb their disappointment in their parents and the world. They not only seek to numb themselves but to elevate themselves to the status of inhumane demigods with no empathy or compassion. Split between his two personalities, Noboru constantly and effortlessly crosses this chasm. Noboru’s life with is mother is down-to-earth and human while his life with his friends is abstract. It may be seen as the theoretical ramblings and fumblings of teenage boys, until they begin to draw real blood.

Noboru’s two worlds are finally forced to confront each other in the figure of Ryuji and the overwhelming emotions he evokes in the boys. When the group learns of Ryuji, they hail him as the ideal man. He is the heroic, rugged archetype of a man’s man: a sailor defined by adventure and bravery, unburdened by the domestic lives they hate so much. They put him on so lofty a pedestal that he immediately falls right off. He fails to meet their ideals at every turn. Noboru takes it upon himself to record Ryuji’s “crimes” down in a book. When the boys learn that Ryuji is giving up the sailor’s life to live with Noboru and his mother, to become Noboru’s father, the chief declares that Ryuji has betrayed Noboru and has “[become] the worst thing on the face of this earth, a father” (162). They then hatch an elaborate plan to “make him a hero again” (163).

The Sailor Who Fell From Grace with the Sea ends right before its climax, before the boys meet out their bloody punishment on Ryuji. The final scene of the novel juxtaposes light and dark. As Ryuji tells the boys the tales of his adventures, he looks out to sea and begins to miss what he is giving up. He grasps the “glory”, the “piercing grief, the radiant farewells” (180) of majestic sea life. In the background, the mountains are bleak and the sun is lustrous. The boys are beginning their work. The puny god sharpen their weapons; they hand him a drugged cup of tea. Meanwhile, Mishima suggests that while Noboru goes along with the group, he is being torn in two by his conscience.

There is a repeating scene/motif in The Sailor Who Fell From Grace with the Sea: Noboru hides in a chest built into the wall of his room and through a peephole, he spies on his mother as she gets ready for bed or sleeps with Ryuji. His mother has no clue this is happening till nearly the end of the book. This motif symbolises the rift between what his mother assumes about Noboru and his friends and what is really happening. The chest is the physical representation of the adults’ blind spot, the ignorant belief that boys will be boys, mischievous but essentially harmless. It is the meeting point of Noboru’s two selves: dark and twisted on one side, light and hopeful on the other.

In the final scene, the chasm between the the two halves of Noboru’s world gets to its narrowest point yet and Noboru has to choose where his loyalty really lies. He has to pick between the concrete, very real life of his new family and the abstract philosophies of his friend group. The Sailor Who Fell From Grace with the Sea therefore shows what happens when youthful arrogance is unchecked, and a group of misguided teenage boys decide that they are god; the brutalities they dream up and the ways they can inflict it on a real and sleeping world.